Koen van de Leur

Read all my blogsHow 'specification by example' can help you get it 'first time right'

When developing software in a team, effective communication is key. Everybody, except maybe the developer working on his own project in his basement, is confronted with the challenge of explaining clearly to others what they think what a software system should do, and what it should adhere to.

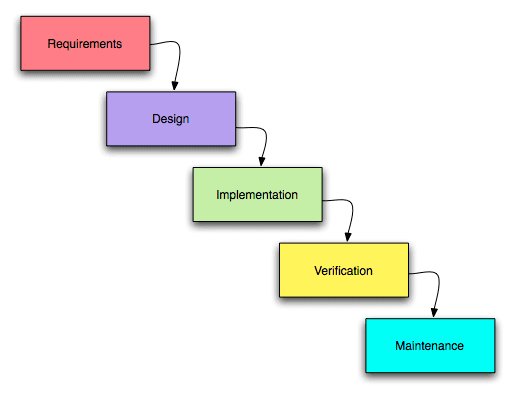

Waterfall

Retrieving, gathering, shaping and documenting software requirements is a specialty in and of itself. The process of requirements engineering is one of the first steps in the waterfall model of software development. It is a process that should bring complex business rules, processes, scenarios, wishes and ideas of different stakeholders together into an effective design. It thus requires both technical and people skills. With a finished requirements document, a team can start implementation. When that’s finished, the system will be tested for acceptance, deployed and maintained. That is, in short, the waterfall method.

Common problems with the waterfall method include changing requirements due to a changing business reality, changes of priority or changes of insight, designs that seem feasible on paper but turn out to be hard to put into practice, and faults that can be traced back to missing or wrongly interpreted requirements. Because of the long feedback loop, faults are often discovered in a late (and expensive) stage. This is why a lot of organisations (both in and outside of IT) have transitioned to Agile ways of working that don’t require one phase to be finished before starting the next, and have much shorter feedback loops.

Agile SCRUM

In order to accommodate a fast-moving business reality, models like Agile SCRUM do not cultivate highly detailed requirements and designs into Big Design Up Front (BDUF). Instead, particular pieces of functionality are increasingly refined as implementation gets prioritised. The advantage here is that less time is wasted on extensively detailing functionality that never makes it to implementation, or doing lots of rework as requirements change.

In practice, one often encounters a product backlog filled with user stories or feature descriptions that haven’t been worked out with requirements and acceptance criteria. However, just like in the waterfall method, these are needed before implementation starts. In a setting like this, how can business stakeholders, business analysts and developers create clear and workable requirements?

Specification by example

One method I personally have experienced as very effective is specification by example. In this method we take a user story or feature description, perhaps with some already defined requirements, and try to think of as many real-world examples on how the functionality would behave in different scenarios. These are then validated against existing business rules and the ideas of various business stakeholders. The examples often unveil differences of understanding or interpretation and are immediately changed. Some examples are not covered at all by requirements, signalling there’s some more work to be done there.

Let’s look at a real-world example of a situation where specification by example could be useful: a business stakeholder wants to introduce the use of coupons in a web shop in order to generate more revenue and customer loyalty. A user story could read something like this:

“As a user, I want to use a coupon online in order to get a discount“

The solution is simple at first sight. A coupon has a value and a unique code. In the checkout, the unique code is used to identify the coupon, and the coupon value is subtracted from the order value. However, some questions immediately arise: should a customer be able to ‘stack’ multiple coupons for a single order? What if the coupon value is higher than the order value? Could a customer then proceed through checkout without any other payment? What happens with the remaining value on the coupon? What happens when returning items; is the customer paid back in coupons?

Asking all these questions is part of the traditional process of requirements engineering, but when applying specification by example, they are conceived into real-world scenarios and tables with examples. Here’s how this could look:

| Original value of order | Coupon value | New value of order | Remaining coupon value | Remarks |

| 80 | 15 | 65 | 0 | |

| 100 | 40 | 60 | 40 | Are remaining coupon values allowed? |

| 50 | 60 | 0 | 10 | Can checkout be completed with final amount of ‘0’? |

| 0,99 | 10 | 0 | 9,01 | Is there a minimum amount? |

| Number of coupons | Usable? | Remarks |

| 0 | Yes | |

| 1 | Yes | |

| 2 | Yes | |

| 100 | Yes | Maximum coupon amount? |

| Original order value | Free shipping (from 30) | Coupon value | New total amount | Free shipping | Remarks |

| 50 | Yes | 30 | 20 | No | |

| 60 | Yes | 30 | 30 | Yes | |

| 25 | No | 5 | 20 | No |

Look how formulating examples can instantly lead to many new questions. Like that, such an exercise can lead to critical assessment, refinement, elaboration or change of the requirements. Step by step, your personal assumptions and interpretations are then replaced with mutual understanding, which in turn produces more consistent requirements.

Specifications have three aims: to establish a shared understanding of the product, to sustain, strengthen, record and back that with documentation, and to provide a basis for testing the product. Specification by example is a collaborative process that primarily focuses on shared understanding. When you have reached an agreement on the right examples, usually those already give you a set of concrete test scenarios and documentation on the intended functionality of the software. Naturally, for this your examples have to be precise, concrete and testable.

Unlike a rather complex requirement that can be interpreted in about five different ways by five different people, a set of examples does not leave much room for assumptions and interpretations. That is another reason why reaching agreement on definitions and common domain language is important. When designing software for clients you often lack some deeper knowledge of the client’s specific domain. With concrete examples the client can give you the necessary context and explain in more detail what problems the software will be expected to solve.

But how exactly can you put this into practice? When you – as developer or consultant – want to express your doubts on a certain functionality, you could show your assumptions in a table of examples and present that, instead of asking an open-ended question. Another method is planning an entire (SCRUM) session to clarify one or several features using specification by example. When you do this, do make sure that business stakeholders, testers and developers are all present (In Agile these are known as the three amigos). For each feature you should formulate some scenarios and write them on a whiteboard. The participants are then asked to write their preferred solution on a sticky note.

Never a waste of time

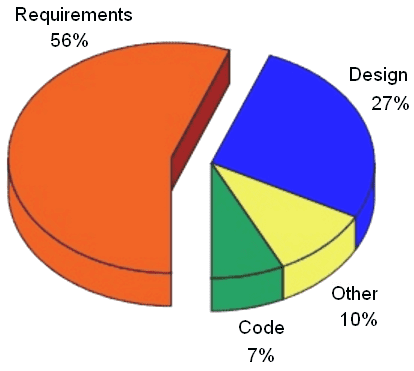

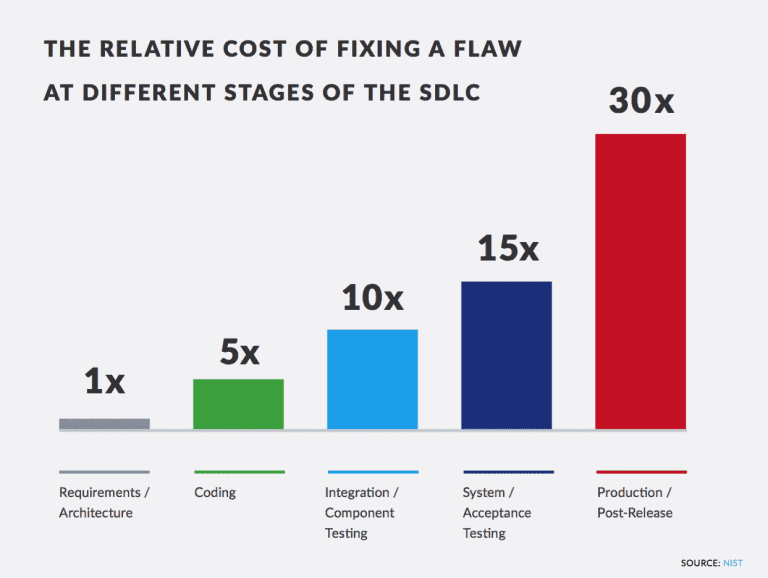

Organising such sessions could be seen as a waste of time. “Not another SCRUM session; the requirements were already formulated, weren’t they?” While in reality they should be seen as investments: because the time you spend in the early stages of a project on clarifying the intended functionality and removing assumptions, will be saved later on in the software development life cycle (SDLC). A mistake that is only found when the system is already in production can be 100 times more expensive to fix than that same mistake when found in the requirements phase (see bar graph). According to several studies most software errors can be traced to this exact phase (see pie chart). So, investing this time is really worth its while.

While I have only described specification by example in aforementioned Agile working environments, where extensive requirements documentation usually is not available, it should be noted that you can also apply it in the waterfall model. Clarity and shared understanding are even more important in longer feedback loops.

Effective application of specification by example has the potential of pleasing everyone involved. The ‘business’ representatives understand what will be built and receive the software they were expecting, the testers are provided with concrete test scenarios, the developers with a clear task and the project manager has fewer delays and interpretation error-based disputes to deal with. Give it a try!